Expert-Tested Tools to Manage Your Child’s Mental Health

5.6.2020 | Seattle Children's Press Team

Managing a child's mental health can feel like an uphill battle with no end in sight. Oftentimes, parents and caregivers feel lost when it comes to navigating through their child's emotions when they are experiencing a mental health crisis or mitigating a situation before, during and after a crisis occurs.

Some of the best resources to help parents and caregivers better understand their child's mental health are the same tools providers routinely use for any patient coming into Seattle Children's with a mental health issue. Developed by pediatric mental health experts at Seattle Children's and used in clinic for over a decade, the escalation cycle is one such tool that parents and caregivers can easily adapt to use at home.

Getting to know the escalation cycle

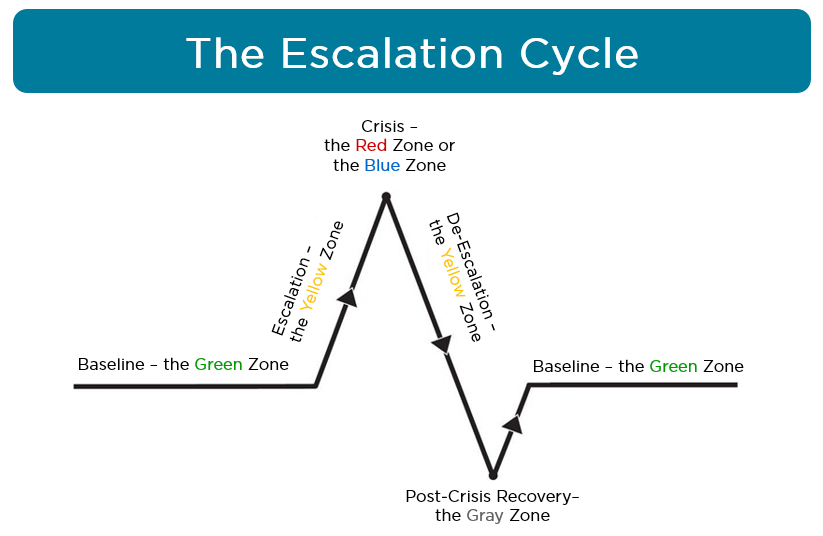

The escalation cycle is a tool used to explain emotion or behavior during a crisis situation. It has six stages identified by different colors. Seattle Children's Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine clinic uses the tool to understand behavior and escalation, and to guide parents and caregivers in using different interventions at each stage. The use of a “Coping Card” together with the escalation cycle is an essential element in understanding the emotions that trigger certain behavior in your child.

“The escalation path and coping cards can help parents and caregivers work with their child to recognize the types of things that upset their child, how their child feels, and what it looks like when they are upset,” said Maureen O'Brien, the director of Seattle Children's Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Unit (PBMU). “This teaches children the skill of self-awareness, which can otherwise be difficult to teach.”

The upward zones: Green, yellow

To understand how the escalation cycle works, it's important to explore each stage of the cycle closely and the interventions that are involved.

Each stage is identified by a color – green, yellow, red or blue, and gray.

The cycle begins with green, which is the baseline. When we are in the Green Zone, our behavior is “normal” or typical, although it looks different for everyone. In this stage, people are calm, rational, and able to learn new skills and have difficult conversations. It is the best time for proactive interventions.

“Interventions are the strategies or activities that we use to help children calm and manage their emotions,” O'Brien said. “Our interventions vary based on the child's level of escalation. Interventions also vary based on the type of trigger — this is when the Coping Card comes in handy. Being aware of the emotion and your child's level of escalation will help you choose your intervention.”

These are some examples of baseline interventions, things you can do when your child is in the Green Zone that will support you when a trigger occurs. These interventions work best as part of a consistent daily routine:

- Make a daily schedule

- Discuss and pre-plan for triggers

- Practice and model coping skills

- Safety proof the home

- Use Coping Cards

- Create a Safety Plan

After a trigger happens, we often escalate and enter the Yellow Zone. Triggers are things that make people feel mad, sad or upset. These are signals that your child needs emotion coaching and coping skills to calm. Without effective coping skills, people can continue to escalate until they are in a crisis. Here are some examples of interventions that can be used during escalation:

- Emotion coach, a parenting tool that can help prevent and lower your child's strong negative emotions and reactions (such as anger, yelling, saying mean things and throwing things) during times of distress

- Try to understand why your child is behaving this way

- Use short words and clear phrases

- Provide distracting coping skills such as watching a movie, reading a book or playing a game

- Encourage your child to communicate assertively to solve the problem

- Help your child with physically calming activities such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, or taking a walk

- Model healthy coping skills – use and talk about your own coping skills

The peak of the cycle: Red or blue zones

When a child continues to escalate past the Yellow Zone, they have reached the peak of the cycle, which is the time when a crisis can occur. In the Red or Blue Zone, we are not able to effectively cope. Crisis is an unsafe period of time; people are often impulsive and reckless. They do not make good decisions when they are in crisis; they often act unsafely toward themselves, somebody else, or the physical space they're in. In crisis, our bodies experience high levels of adrenaline, making crisis a phase that is physically hard on our bodies.

There are two types of crises: externalizing or Red Zone crisis, a behavior is directed at others (either aggression or property destruction) and internalizing or Blue Zone crisis, a behavior is directed at themselves.

During this phase, the only focus is on safety using these strategies:

- Follow a Safety Plan

- Use short words and clear phrases

- Make your surroundings as safe as possible

- Have only one person do the talking

- Give space, while providing appropriate supervision

- Utilize a crisis line or 911 if the situation becomes so unsafe that you need more help

The downward zones: Yellow, gray, green

After the crisis has passed, people de-escalate and reenter the Yellow Zone, which can be a volatile phase. People are calming down and trying to burn off the adrenaline from the crisis. It can take over thirty minutes for your child's body to return to baseline.

“This is where families often make the biggest mistake,” O'Brien said. “They try to problem solve and don't wait until their child is back to their baseline. This is a crucial period when a child needs time to recuperate to get their energy back and let their adrenaline run-off.”

It is best to use calming coping skills, such as:

- Activities that use up energy and are socially appropriate, like going for a walk or playing outside (not activities that encourage property destruction or aggression)

- Use as few words as possible and do not talk about what just happened

- Provide your child with a coping skill without speaking (for example, model coping skills or bring them a drink or stress ball without asking)

- Role model a coping skill, get a drink of water yourself or grab another stress ball when you bring them one, and use it in front of them

- Encourage distraction coping skills

- Do not problem solve

The Gray Zone is a time for post-crisis recovery. Before people are back to their baseline and feeling “normal” or typical, it is common for them to have low energy and feel guilty, tired, hungry, sad or embarrassed about the crisis. In this phase, people continue to feel the run-off of adrenaline. Your child may be physically and emotionally exhausted. Focus on caring for your child by:

- Providing drinks or snacks as needed

- Continuing to give space if needed

- Turning down the lights (to help them rest)

- Avoiding problem solving and discussing consequences

“Often families forget the gray zone and want to take this time to talk about the crisis right away,” O'Brien said. “This is a period where a child is in the most risk of re-escalation. Give your child time to get re-grounded and back to their normal behavioral patterns before discussing the situation.”

Finally, after the Gray Zone recovery period, when people recover from the aftermath of the adrenaline, or the post-crisis “slump,” they return to their baseline or the Green Zone. They are calm, stable, and able to learn again. At this point, you can discuss next-steps with your child, focusing on how to prevent the same crisis from happening again. Here are some examples of interventions you can use after your child returns to baseline:

- Discuss the triggers that led to escalation

- Identify the coping skills they tried and why they did or did not work

- Brainstorm coping skills that may work better for the trigger(s) in the future

- Update Coping Card and/or Safety Plan

- Outline consequences or follow up actions (emphasize natural consequences, e.g., if they broke the TV remote when they were angry, they will need to replace it from their allowance and/or not be allowed to watch TV for a period of time. However, try to make the consequence match the behavior, not be “punishment” for the sake of punishment).

A guiding resource

The escalation cycle and Coping Cards used by Seattle Children's have helped thousands of patients and their families through the most difficult situations.

“Created based on psychological research and various other medical literature that exists, the escalation cycle is formatted in a way that is unique to Seattle Children's,” O'Brien said. “What makes this tool so useful is that children of any age can benefit from using them. This is one of our standard interventions we use and one of the things that makes our mental health program in our Emergency Department (ED) distinctive compared to others. While other EDs may do assessments and make a determination plan for a patient, they don't always have resources or skills to provide education to help families stay out of crisis when they leave.”

While these tools are significantly helpful, O'Brien says families should complement them with the knowledge of knowing their child and what's best for them.

“The biggest takeaway for families is that ‘you know your child best,'” she said. “These tools are not meant to tell you what do or say when your child is undergoing a mental health issue; these tools exist to guide you in the right direction and understand their emotions on a deeper level.”

If you, your child or your family needs help right away, call your county's mental health crisis number. In King County, call 866-427-4747. You can also text HOME to 741741 or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 800-273-8255, from anywhere in the U.S. If you or a family member has a problem with a substance use disorder, please consider calling the Washington Recovery Help Line, 866-789-1511.