Seattle Children’s Uses 3D Printing to Plan Complex Surgeries, Creates Custom Care Model

6.29.2021 | Seattle Children's Press Team

Photo courtesy of Four Oaks Photography.

Photo courtesy of Four Oaks Photography.

On January 30, 2019, Nia Mauesby was born. To celebrate her arrival, the setting sun illuminated the Seattle skyline with bright hues of red, orange and yellow. It was one of the most dazzling and memorable sunsets of the year. As quickly as the setting sun dipped over the horizon, the winds began to shift, and the foreboding weather foreshadowed the turbulent journey that lay ahead.

“When my water broke, we had no idea what we were in for,” Reem Mauesby said.

Mauesby and her husband, Timothy, were elated for their daughter’s arrival, but the timing couldn’t have been worse. Stricken with the flu, Mauesby wasn’t able to see her baby girl for 24 hours after giving birth. When Nia was finally was placed on her chest, she felt a heavy sense of relief, but that feeling would soon be stripped away.

Mauesby noticed Nia’s skin was very dark, much darker than her two older brothers when they were born. She wasn’t getting enough oxygen and was taken to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Valley Medical Center. As a pediatric intensive care nurse, Mauesby knew almost everyone on the unit. She wasn’t concerned at first.

“It happens all the time,” Mauesby said. “I thought to myself, ‘she’ll be fine.’ I pushed too fast and she wasn’t able to get fluid out of her lungs. That’s all it was. It’s nothing serious.”

For two days, Nia was on oxygen and watched carefully in the NICU. Mauesby never left her daughter. They stayed in the NICU for five days before finally getting discharged. That night, with a snowstorm approaching, they wanted to get out of the unit before the roads became too hazardous for travel.

For two days, Nia was on oxygen and watched carefully in the NICU. Mauesby never left her daughter. They stayed in the NICU for five days before finally getting discharged. That night, with a snowstorm approaching, they wanted to get out of the unit before the roads became too hazardous for travel.

Once they were home, Nia showed signs of labored breathing. When she would breathe out, a whistling sound would emanate from her tiny lips. Mauesby called the emergency department and the NICU doctors where she had given birth. They gave her the option of waiting until her daughter’s pediatrician appointment scheduled for the end of the week or coming to the emergency room. When Mauesby hung up the phone, the whistling stopped. Relief flooded over her, but it was short-lived. A couple of days passed, and Mauesby’s concern grew once again.

“Everyone kept telling me she was fine,” Mauesby said. “But I knew something was wrong.”

“Get Comfortable”

Mauesby had previously worked as a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) nurse at Seattle Children’s. She couldn’t shake the feeling something wasn’t right, and so she sent a video of Nia breathing to a doctor she used to work with. “You need to bring her in immediately,” Mauesby recalled the provider saying. Mauesby called her parents and they drove through snow to help so she and her husband could take Nia to Seattle Children’s Emergency Department.

Once they arrived, doctors hooked Nia up to monitors and checked her oxygenation level. They also did a CT scan. When the results came back, they told them to get comfortable. They weren’t leaving any time soon.

“There were doctors, nurses, and residents all coming in and out of the room to look at the CT scan,” said Mauesby. “When they showed it to me, it felt surreal. I didn’t believe it was real life.”

In medicine there is a saying, ‘when you hear hoof beats, think horses, not zebras.’ The motto is a reminder to first think about the most likely possibility before jumping to something rare. Mauesby had been taught that lesson.

“As a nurse, they always tell us, what you’re seeing is rare,” she said. “All kids are not like this. Don’t make this your whole world. But in that moment, that became my world. I was that family.”

“She’s Unique”

Nia’s diagnosis was bronchial stenosis, a narrowing of her right bronchial tube so severe she couldn’t breathe effectively. Mauesby said her daughter’s bronchus was the size of a hair.

“The air has an easier time going into the lung then it does coming out,” said Dr. Kaalan Johnson, an otolaryngologist at Seattle Children’s. “The lung on the right gets much bigger than it should be. It pushes the other lung and the heart all the way over into the left chest, and so when you look at the CT scans, you see this tiny sliver of a lung on the left side and a really huge lung on the right side. It doesn’t move air effectively to allow for her to breathe comfortably and grow.”

Mauesby remembers the moment Johnson walked into the room. Still in shock, she looked up to see Johnson’s tall figure walking toward her, a calm and reassuring presence surrounding him.

“Your daughter’s condition is very unique,” he said. “But it’s going to be okay.”

Mauesby said at the time, she didn’t realize Johnson would be their person. He’d be one of their many heroes.

A Rare Procedure for a Rare Case

Nia underwent a highly complex surgical procedure to rebuild her airway before she was even a year old. Today, she is thriving, thanks in part to a cutting-edge technology helping surgeons provide better care and better outcomes.

Nia underwent a highly complex surgical procedure to rebuild her airway before she was even a year old. Today, she is thriving, thanks in part to a cutting-edge technology helping surgeons provide better care and better outcomes.“Once we confirmed what type of narrowing we were dealing with, we were then able to talk about the type of surgery she would likely need,” Johnson said. “The first step was getting the whole picture of what was going on, and then trying to make sure she was in a safe and healthy state to undergo the procedure.”

Like many Seattle Children’s patients, Nia’s health care needs were complex and required extensive coordination amongst many providers. After careful consideration, a surgery called a slide tracheoplasty was determined to be the best option for Nia. The surgery is incredibly complex. The patient is placed on ECMO, a form of heart-lung bypass. An incision is made on the chest to access the airway. During the surgery, the trachea is cut and is slid up onto itself, creating a larger airway. The surgery requires a team of specialists across disciplines, including otolaryngology, cardiology, pulmonology, anesthesiology and more.

Seattle Children’s otolaryngologists perform multiple slide tracheoplasties every year, but it’s far less than other procedures. For comparison, they perform thousands of tonsillectomies every year.

Committed to Outcomes

For procedures like a slide tracheoplasty, precision is imperative.

For procedures like a slide tracheoplasty, precision is imperative.

“That very first step of dividing the windpipe is something you can’t walk back from,” Johnson said. “You need to know exactly where to cut and at exactly what angle.”

Today, with the help of a new multi-material 3D printer, Seattle Children’s surgeons and care teams are able to map out complex surgeries and practice intricate surgical techniques before ever entering the operating room. This custom care approach helps provide better, safer treatments.

“Each specific case is unique,” Johnson said. “The exact location of the stenosis, the degree of narrowing, the position, these factors all impact our approach to surgical planning and decision making. We have embarked on a protocol in which we 3D print each of the slide tracheoplasties ahead of time, so we have life-sized models of the child’s airway to evaluate and practice on. There is something that is specifically valuable in our experience in having something you can touch and feel and move around in your hands. When you’re dealing with the airway of a tiny baby, it’s a constantly moving, soft, flexible structure. Being able to hold a model in your hands and perform the actual procedure alongside your peers, allows critical discussions and learnings to take place.”

Adding Value for the Patient and Family

Johnson gave the family the option of being referred to another hospital that pioneered the slide tracheoplasty procedure. After consideration, Mauesby and her husband said they trusted Johnson and his team at Seattle Children’s, and decided against traveling across the country for care. They put their hope in the hands of Seattle Children’s.

Surgeons can practice complex procedures on realistic, 3D printed models are as unique as their patients’ anatomies.

Surgeons can practice complex procedures on realistic, 3D printed models are as unique as their patients’ anatomies.“Seattle Children’s is a fabulous hospital,” she said. “They made us feel very comfortable. I was always included in every decision. I was part of the team. I loved working at Seattle Children’s, and I loved being a patient. Our care team became our family.”

Mauesby said during their darkest days, Johnson and other providers in the NICU were always there for them. Mauesby recalled one specific night Nia was having trouble breathing. She was feeling anxious and called the nurse for help. Doctors and nurses came shuttling into their room to check on her. One of Johnson’s colleagues was on call that night.

“I remember calling Dr. Johnson and telling him I was really scared,” Mauesby said.

It was around midnight. Johnson had left the hospital for the day, but he turned around and came back. Johnson accompanied his colleague taking Nia into the operating room to check her airway.

“I knew it was important to be in the room with Nia,” said Johnson. “I wanted to be able to reassure their family.”

A Second Home

In total, Nia was in the hospital for three months. It took some time for Nia to grow enough to safely undergo the slide tracheoplasty. She was the smallest patient to ever undergo the procedure at Seattle Children’s. The surgery was planned for April 5, 2019.

Leading up to the surgery, Mauesby said there were moments she broke down emotionally.

“I would look at her and think, ‘I can’t live without her,’” Mauesby said. “I prayed and promised I wouldn’t ask for anything else if she would just make it through this. I needed her to be okay. I couldn’t lose her.”

One night, while her older son was sleeping, she began to cry. As tear flowed down her cheeks, she noticed her son looking at her.

“She’s going to be okay, mom,” he said.

And he was right.

Johnson and his team sat down with Mauesby and her family to go over each and every intricate detail of the surgery. They even printed a multi-colored 3D model of Nia’s airway to show them where they would make the incision and how they would repair the abnormality.

“When Dr. Johnson gave me the model it made me so happy,” Mauesby said. “Looking at it and seeing her airway was really special.”

The Big Day

The night before the surgery, Mauesby and her husband met with their care team once more. Then afterwards, the surgeons huddled together in a conference room to walk through the surgery with all of its clinical and procedural complexities. They practiced making the incision and suturing up the tiny 3D models. Everyone in the room felt prepared for what was to come in the operating room.

As she was taken into the operating room, Mauesby and her husband said goodbye to their daughter. They hugged her, sang to her and kissed her one last time. Mauesby remembers uncontrollably crying. Those were the longest hours of their life. It was a trying experience because Mauesby has been in those operating rooms. It broke her heart thinking about her daughter on the operating room table.

“I worried we might lose her,” she said.

Thankfully, everything went exactly according to plan.

“Seattle Children’s is the best place ever,” said Timothy Mauesby. “I couldn’t imagine being anywhere else and going through that experience. The whole care team was our family. Dr. Johnson was going to do everything in his power to make sure she came out better than when she went it. It was going to be successful. Looking at her now, it’s like it never happened. It’s a dream. It’s like we’re back to our life again. When I look at her, I can’t believe we got through it. We made it.”

Mauesby prepared herself to see Nia for the first time. She explained to her family that she would have tubes in her body, and she may not look as she normally would. When she walked into the room though, she was astonished.

“She was so beautiful,” Mauesby said. “The most beautiful I had ever seen her.”

For the first time, Nia was pink. She was finally getting enough oxygen.

Leading in Innovation

Behind the scenes creating the digital and printed models and serving as one of many champions of Seattle Children’s new service called Custom Care is Seth Friedman, Ph.D., manager of innovation imaging and simulation modeling at Seattle Children’s.

Seth Friedman can create anatomical models that are unique to each patient, from tiny airways to squishy hearts.

Seth Friedman can create anatomical models that are unique to each patient, from tiny airways to squishy hearts.After years of outsourcing and refining the printing process, in 2020, Seattle Children’s purchased a J750 Digital Anatomy printer, which has unprecedented ability to create anatomical models that mimic the feel and properties of actual tissue. This allows models to be made that are increasingly complex and life-like, helping to advance surgical care from a patient-specific, training, and research perspective. Seattle Children’s is the only pediatric hospital in the Pacific Northwest that has the Digital Anatomy Printer.

“The earliest 3D models printed in TissueMatrix material were instrumental for understanding the optimal fit for a custom tracheostomy tube, something that would have been impossible a year ago,” Friedman said.

According to Friedman and Johnson, the opportunities and applications are vast, but the objective is always the same: to provide the best possible care.

“3D printing is one part of our goal to better prepare our teams and personalize how we care for complex surgical patients,” Johnson said. “In some ways, these models are not monumental advances. We can do the surgery without it as we did before. But we are getting to the point where we’re personalizing care in ways that delivers the best possible patient care and outcomes.”

Miraculous Outcomes

Today, Nia is 2 years old and thriving.

Today, Nia is 2 years old and thriving.

“You would never know what she’s been through,” her father said. “She has a tiny scar and that’s all.”

Nia had no complications after the surgery and recovered very well.

After leaving Seattle Children’s, they had follow-up appointments, but so far everything has been perfect.

“Her future is bright,” Johnson said.

Since being discharged, Mauesby said she’s stayed in touch with the care team that became like family.

“We’re so incredibly grateful for everything they’ve done for us,” Mauesby said.

When Nia turned 1 years old, Mauesby said she sent photos to Johnson. She felt blessed to have the opportunity to celebrate the milestone. Nia had come so far in a year, and she has boundless potential.

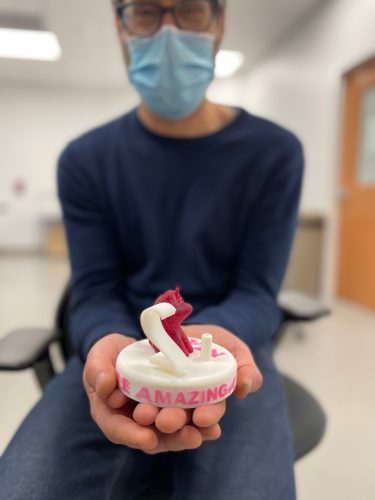

To celebrate her birthday this year, Nia’s care team planned something special for her. They knew how much the 3D printed airway meant to Mauesby and their family, and so they created a one-of-a-kind birthday present to celebrate the milestone. The theme of the birthday party was unicorns, so Friedman created a custom unicorn candle holder to sit atop her birthday cake.

“This was one small thing we could do to make Nia and her family feel extra special,” Friedman said.

Transforming Care

Seth Friedman designed a custom unicorn cake topper to help celebrate Nia’s birthday.

Seth Friedman designed a custom unicorn cake topper to help celebrate Nia’s birthday.Nia isn’t the only patient to benefit from 3D printing. The custom care approach has been used to help surgeons and care teams plan many complex surgeries at Seattle Children’s, across many specialties.

When Grace Heater was 4 months old, her family traveled across the country for care. Diagnosed with a severe form of Apert Syndrome, her complex and rare craniofacial condition required a hospital with multidisciplinary and coordinated care. They put their trust in Seattle Children’s.

Dr. Randall Bly, an otolaryngologist at Seattle Children’s has worked closely with Grace and her family for years. What drives him is his dedication to doing what’s best for every family. With a background in engineering, he enjoys finding innovative solutions to complex problems.

“People often ask me, ‘When did you switch out of engineering?’ And I usually say, ‘I never did, and I’m still doing engineering and medicine.’ By using 3D printing, we’re seeing things that we didn’t see on the computer. This is a way to make sure we’re doing the right thing for the patient. It helps provide confidence and that we’re able to do the best surgery we can for the patient, and with the least number of surgeries. Patients are the whole motivation behind this approach.”

In total, Grace was inpatient at Seattle Children’s for more than three years. She’s undergone more than 50 surgeries and has required a vast team of specialists across many specialties including neurosurgery, spine, hand and foot, craniofacial and more.

“Her airway is very abnormal. It’s narrow and twisted,” Bly said. “Sometimes the airways are formed in a way that are abnormal and these babies need a trach tube. A trach tube can be lifesaving. However, sometimes the standard trach tubes don’t fit in these airways because they’re not normal sized and are very unique.”

According to Grace’s mother, Saskia, her airway was the size of a coffee stirrer.

3D printing was instrumental in helping Grace’s care team create a trach tube to fit her unique airway. Bly says incorporating 3D models helps produce better outcomes.

After spending three years in the hospital, Grace was finally able to leave for the first time. Her care team cheered and coordinated a bubble discharge party.

After spending three years in the hospital, Grace was finally able to leave for the first time. Her care team cheered and coordinated a bubble discharge party.“He would pull the model out of the pocket,” she said laughing at the recollection. “He constantly had it with him.”

“My goal is to listen to patients and families and understand the problem,” Bly said. “This helps me guide families to make the best decision for them. It is a privilege to treat patients and families, and I will always make sure that they are cared for in the best possible way.”

“They took care of us,” Saskia said. “They cared for our whole family and took our stress away.”

Grace required a slide tracheoplasty as well. Her surgery was planned using 3D models, and thanks to the success of that operation, she reached a major milestone: leaving the hospital for the first time.

In September, that dream was realized. Her enormous care team celebrated the discharge with a bubble party and a poster of a big yellow bus, her favorite song.

“It didn’t seem real. We couldn’t believe we were leaving,” said Saskia.

Cheers erupted on the unit as Grace wheeled out of her hospital room, a big smile on her face.

“She’s an incredibly special little girl,” Bly said.

To their care team, they have so much gratitude.

“Thank you for getting creative. For going above and beyond to care for Gracie,” she said. “It made all the difference. She’s still here. Everyone stuck through it with us, even when it looked like she might not make it.”

The Future of 3D Printing

“To be a good surgeon requires excellent communication with families,” says Dr. Kaalan Johnson, shown here with Reem and Nia. “You’re trying to understand the value system of the family and what you can offer to improve their quality and quantity of life. To fully understand that and commit to that, you have to be able to communicate complex concepts. That’s where 3D printing has added value.”

“To be a good surgeon requires excellent communication with families,” says Dr. Kaalan Johnson, shown here with Reem and Nia. “You’re trying to understand the value system of the family and what you can offer to improve their quality and quantity of life. To fully understand that and commit to that, you have to be able to communicate complex concepts. That’s where 3D printing has added value.”

The custom care model is one exciting advancement Seattle Children’s is utilizing to improve outcomes and provide better care to patients and families across a broad range of specialties.

As Friedman says: “The ability to create life-like materials and multiple tissues within a single print has the potential to transform the way we deliver complex care. At a personal level, what is most motivating is playing some small part in the care we can give to complex patients like Nia and Grace.”

Photo courtesy of Four Oaks Photography.

Photo courtesy of Four Oaks Photography.“To be a good surgeon also requires excellent communication with families,” Johnson said. “That shared medical decision making is vital. You’re trying to understand the value system of the family and what you can offer to improve their quality and quantity of life. To fully understand that and commit to that, you have to be able to communicate complex concepts. That’s where 3D printing also has added value.”

For more than a year, Mauesby has carried around the 3D printed model of her daughter’s airway that Johnson gave her in the weeks leading up to her surgery. She takes it with her wherever she goes. The small piece of malleable plastic may not seem extraordinary at first glance, but it means the world to Mauesby.

“One day, Nia is going to have the most amazing item for show-and-tell,” Mauesby said with a proud smile. “She’ll be able to hold up the model and show people exactly how far she’s come.”

Her mother describes Nia as a warrior.

“I know she’s meant to do great things,” she said. “She can do anything she puts her mind to.”

Photo courtesy of Four Oaks Photography.